In Lambda School, we are given a five-week long project to work on with other students. This is cross-discipline project, so data science students work with web dev students.

In my case, I got assigned to the development of a website called So-Me. The website is a social media management website, and were looking to incorporate more features into their Twitter account management service.

After talking with my teammates, we came up with the idea of using natural language processing to analyze the post that your followers engage with the most. We thought this could be a potentially useful tool for those looking to increase engagement on Twitter, since it could, potentially, tell you what kind of topics would likely lead to more retweets and comments from your followers. It was later decided that the results of this topic modeling process would be displayed on an “analytics” tab, along with other values calculated by the data science team’s API.

The first major decision we made was to switch the backend API from Flask to FastAPI, a tool that we had been recently introduced to and seemed well suited for our task. Since the existing code base was small, it was not terribly difficult to make the swap and move exiting code over. The second thing we decided on was hosting the API on AWS, something we decided on as a resume-driven development choice. We knew working in AWS at least once would look good in the future, and we might not get the chance again!

The main challenge imposed upon us was the rate limiting in the Twitter API itself. To collect the data we need for each individual user, we needed the Data Science backend API to do the following:

1) Get a list of the user’s followers on Twitter. 2) For each follower, get the last 500 posts in their timeline. 3) For each post in their timeline, add the “parent” post to a list if it’s a retweet or a comment and it’s less than a month old.

This would, effectively, get a list of all the posts your followers are engaging with. The results would then be applied to a topic modeling algorithm, which we thought would be the most time-intensive part of the process. We were wrong. It turns out, Twitter does not like you making too many requests in a short time span, and will have you wait until your number of requests has refreshed, usually around 15 minutes. It would not be uncommon to hit this rate limit multiple times in the process of gathering data for a Twitter account with lots of followers. This made the act of fetching data take MUCH longer than is acceptable for an API request.

To compensate for this, we had to develop a queue system instead, with the act of scheduling this data gathering being an asynchronous request to be added to the queue.

Eventually, we got something working, although in hindsight it would have been better to have designed a worker app with something like Celery that handled this data gathering separate from the API app. We didn’t know how to do that at the time, it was something I only learned was an option later.

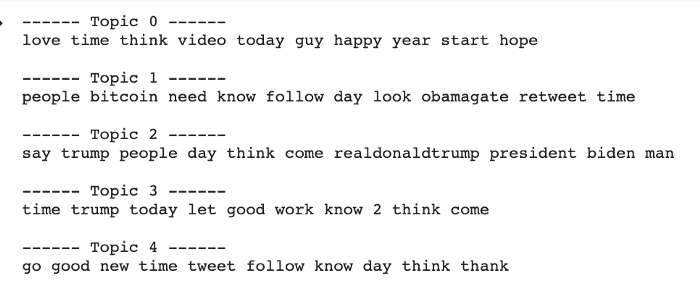

The next step was the actual topic modeling. For this, we used the library Gensim. We had many discussions on what was the best way to present the results, but in the end, we decided on the following:

1) Using Gensim, we would apply topic modeling on the list of posts, creating five separate topics. 2) Each topic would be represented by the top ten words that had the highest correlation to that particular topic. 3) The API would return each topic as five arrays, each containing ten words.

We spent a long time fine-tuning this process, but eventually we started to get noticeable results. Topics become somewhat ‘coherent’; for example, at one point we saw a topic pop up with the words “contest”, “sweepstakes”, and “retweet”, implying a trend of people retweeting promotional advertisements.

One of the interesting troubles that came up was the fact that we were performing this experiment during a time when America was having a number of police related protests all over the nation. It seemed like it was all anybody on Twitter was talking about at the time, and it showed in our data, with words like “police” and “shooting” popping up in nearly every category. While this might be useful information to some, we expected some clients would rather exclude these kinds of words from their results. This prompted us to add a “stopwords” feature to the topic modeling API, which would allow users to specific which words they would like to be ignored during the topic modeling process. Our testing showed that this was helpful in tuning out certain overwhelming political topics that clients may not be interested in.

This project was a challenge, and we worked with many new tools during its development, but in the end we were proud of the work we had done on So-Me.