During the first “build week” of the computer science portion of my Lambda School education, I was given the option to program from scratch one of several popular algorithms used in data science. After looking through them, I decided DBSCAN would be an interesting choice.

DBSCAN is an algorithm used to cluster data points based on their distance away from each other. It’s similar to K-Means Clustering, and can be used in similar situations. In some ways, it performs better, but with a few drawbacks, which I will cover later in this article. There’s actually plenty of resources on DBSCAN, although most of them will simply list the features of the algorithm, when is the best time to use it, and then tell you that you don’t really need to know how it works… just import it from some library and use it.

I think that this is a poor approach, since understanding how an algorithm works will help you utilize it more efficiently. For example, one parameter you need to make DBSCAN work properly is epsilon… but what does it do? What’s a reasonable value for it? This becomes more clear as you understand how the algorithm actually groups up data points.

The DBSCAN algorithm needs two parameters: epsilon and minPoints. Once you give these values, the algorithm starts to look for three kinds of data points: core points, where it has enough points around it to both get a label and spread that label to all its neighbors; border points, which are close enough to core points to have a label but doesn’t have enough neighbors to spread the label to all its neighbors; and noise points, where it’s not in any cluster at all.

1) Pick a point, and find all neighbors within epsilon distance to it.

2) If the number of neighbors (including the original point itself) is less than minPoints, label it as “noise” (usually this means a label of -1) and move on to the next point. Otherwise, you’ve found a “core” point and can apply a label to it and all of its neighbors, even those previously labeled as “noise”.

3) If any of the neighbors also has minPoints neighbors, then you’ve found repeat steps 1-3 recursively with this point, applying the same label to it to add more and more points to the group. This repeats until you’ve found all core points in this cluster.

4) At the end of this loop, you move on to the next unlabeled point, repeating steps 1-3 once more with a brand new label. Repeat until there are no unlabeled points.

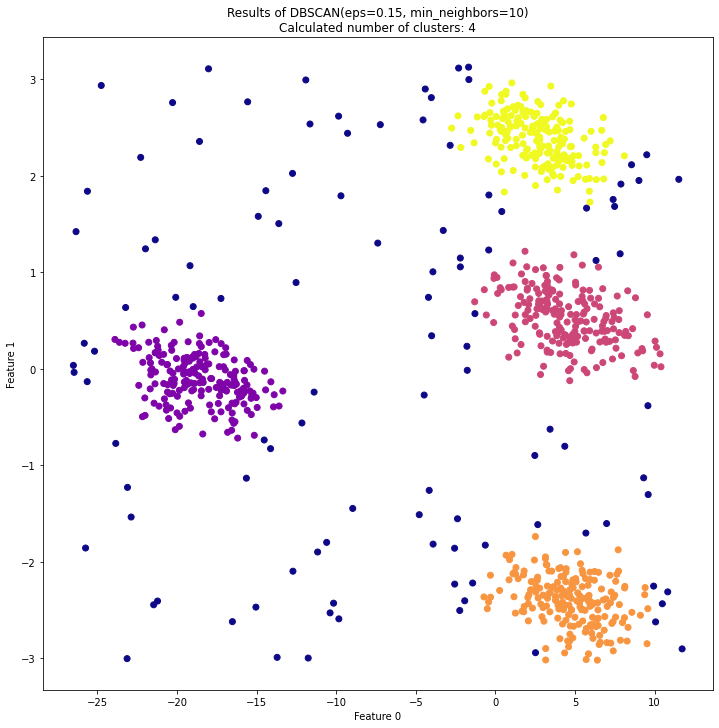

At the end of this procedure, you end up with a labeled dataset, such as the one shown above. Unlike K-Means Clustering, the DBSCAN will label points that do not reliably fit within a cluster, which might be helpful in some applications. Additionally, DBSCAN is better at finding clusters of unusual shape, and is much less likely to split datasets in half. However, unlike K-Means, the number of clusters, K, is not defined… if you want a specific number of clusters, you have to play around with the value of Epsilon until you get it right.

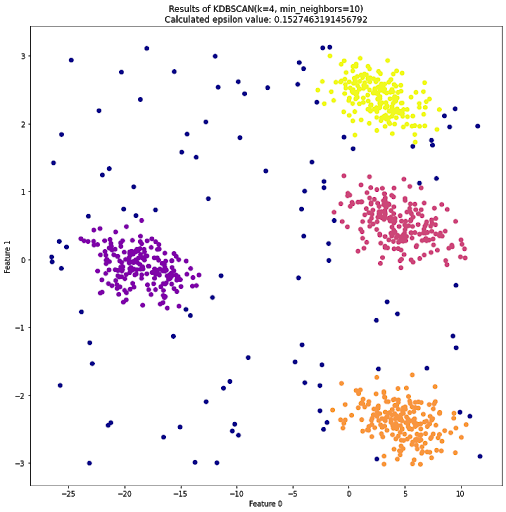

To address this potential shortcoming, I created a potentially useful algorithm that is based on DBSCAN, yet will attempt to label a dataset with K clusters. I call it K-DBSCAN.

Someone has almost certainly made this before, but what the hell, let’s pretend I’m a genius and invented something clever and new.

Here’s how K-DBSCAN works. First, you give the function a value for K, as well as the minimum number of neighbors like before. It will then apply a search pattern similiar to a binary search to find an epsilon value somewhere between the shortest distance between two points and the largest distance between two points.

For each guess, it splits the current range it’s searching in half. If the guess creates too few clusters, it looks at the lower half, and if it creates too many, it looks in the upper half. Eventually, it should find an episilon value that results in K clusters.

This search pattern is not perfect, since the relationship between k and epsilon is not linear. However, it will usually give you a good idea for an epsilon value you will want to use.